Today we’d like to introduce you to Francisca Orellana Polanka

Alright, so thank you so much for sharing your story and insight with our readers. To kick things off, can you tell us a bit about how you got started?

Oveja Negra Kids was born as a response to the ban on ethnic studies in Arizona in 2011 and 2012. At the time, I was in college, and many of my friends had started their own families. I began creating Latin American dolls accompanied by small booklets that provided biographies of historical and cultural figures such as Frida Kahlo, Mercedes Sosa, and Víctor Jara. These booklets also introduced terms that were often excluded from school curricula—concepts like heteronormativity, neoliberalism, and the Mexican Mural Movement—along with geographical and historical context.

Over time, these booklets evolved into comprehensive educational materials designed to spark meaningful discussions at home about politics, history, culture, art, and traditional music. My goal was to provide families with resources to engage in important conversations while embracing their cultural heritage. I wanted my friends’ children—and children everywhere—to grow up feeling proud of their identity and history.

Without ethnic studies, many children grow up believing their culture has little connection to modern American society. The achievements and contributions of Latin America, such as the invention of color television in Mexico, are rarely acknowledged. People often underestimate the power of representation and its profound impact on a child’s self-esteem. In a short time, what began as a personal project turned into a full-fledged business, and with it, my passion for creating educational materials truly took shape.

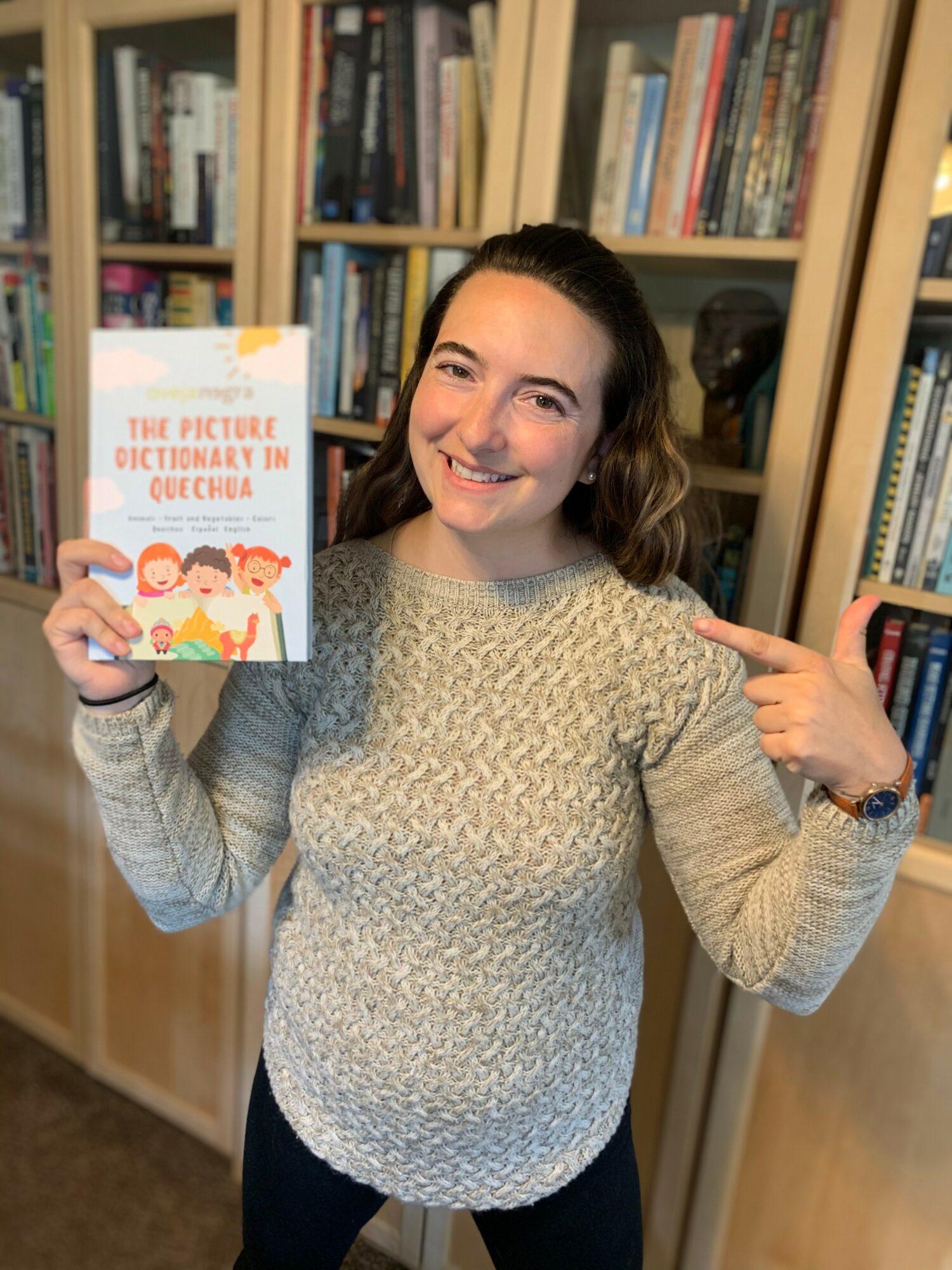

As an anthropologist and sociologist, my greatest passion is taking complex concepts and making them accessible to children of all ages. I am especially committed to preserving Indigenous languages. I spent months in Cusco, Peru, conducting ethnographic research, learning Quechua, and studying Andean history. Since then, I have developed numerous picture dictionaries and workbooks for children in various Indigenous languages to encourage multilingualism and cultural preservation.

More recently, my focus has shifted toward books on civil rights, civics, and American history—many of which will be released in the coming months. I am also working on translating existing books and ensuring that my materials are widely accessible, offering copies in Braille upon request.

At its core, my mission is to make knowledge, culture, and language accessible in every sense of the word. I believe inclusivity is the foundation of meaningful education—ensuring that all children feel represented, valued, and empowered to embrace their roots. A child’s confidence is deeply tied to their ability to take pride in their heritage.

Today, Oveja Negra Kids offers a diverse collection of books, including:

Animal conservation (books and coloring books)

Indigenous languages (picture dictionaries and workbooks)

Asian cultures (language workbooks and Khmer folktales in both English and Khmer)

Civics and history (books for elementary and middle school students)

Ethnographic studies

This collection continues to evolve to meet the ever-changing needs of our society. Every book I create is an act of love, resistance, and advocacy for marginalized cultures and languages.

The name Oveja Negra—meaning black sheep—symbolizes my belief that today’s black sheep are those who read, stay informed, and embrace cultural diversity. Although I am no longer making dolls and toys, my focus remains on developing educational books that are both engaging and accessible.

I am an American born abroad, meaning I was born and raised in Chile to an American family, and my upbringing deeply shaped my perspective on culture, language, and identity. As a teenager in the States, I remember how impactful it was to see even the rarest representation of Chilean-Americans in pop culture. I want children to see themselves in a more positive way in pop culture, at school, in history books and anywhere else. By normalizing diverse cultures and languages in homes across the world, we foster a more inclusive and enriched society—one where every child feels seen and valued.

I’m sure it wasn’t obstacle-free, but would you say the journey has been fairly smooth so far?

My journey with Oveja Negra Kids has not been a smooth one. Much like my work in social justice and advocacy, my publishing work has often been reactionary. The topics I choose to write about are frequently in response to laws, bans, or a broader dissatisfaction with prevailing political ideologies. You could see it as a never-ending source of inspiration—if you want to be optimistic—but on the other hand, it is also a reflection of the pendulum swinging toward racism and intolerance. And we can all agree that such shifts are both damaging and exhausting for the soul.

Becoming a mother profoundly reshaped my perspective on the importance of early education. As an anthropologist, my love for cultures, languages, and history is matched only by my desire to see a happy, healthy generation of children grow up with self-esteem, kindness, and an openness to different backgrounds. I want kids to see everyone as equals, to appreciate diverse languages and accents, and to embrace cultures beyond their own. That kind of inclusivity can only be nurtured if children are exposed to it from an early age.

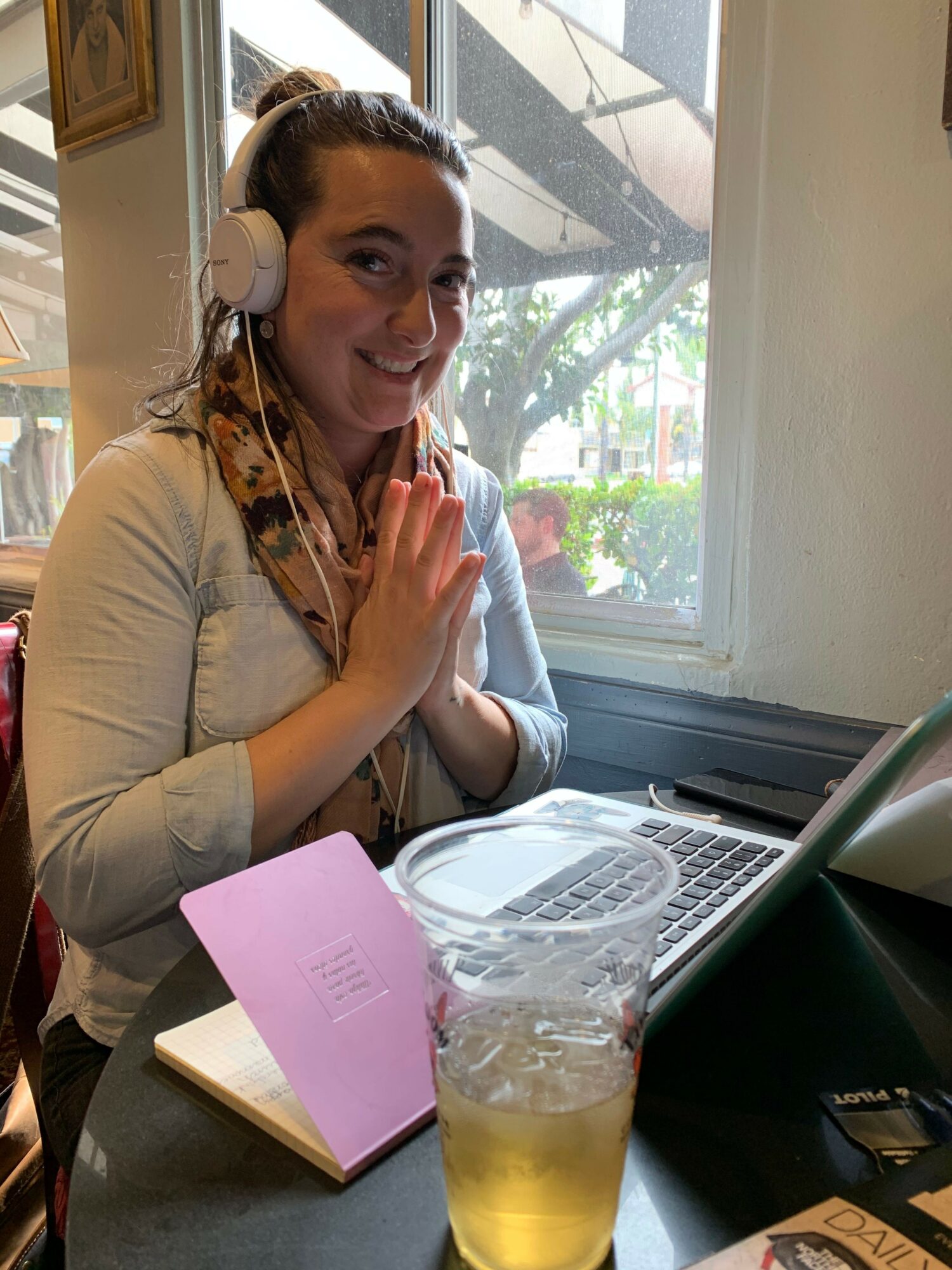

This is why I created trilingual picture dictionaries. I wanted my own child to grow up immersed in multiple languages, developing a natural receptiveness to multilingualism. But as any mother knows, finding the time to research, write, edit, illustrate, and publish is a challenge in itself. My greatest struggle as a creative is learning to accept that my work must fit into the small pockets of time my children allow.

I would love to have the space to develop projects without the constant urgency created by political events. But the reality is that my work—and my passion—exists in direct response to the world around me. In that sense, I am both my greatest strength and my biggest challenge. I have ADHD, which is both a blessing and a curse when it comes to completing projects. It fuels my creativity and drive, but it also means I’m constantly navigating the challenge of focus and follow-through.

Despite these challenges, I remain committed to my mission. The need for inclusive, accessible, and empowering educational materials has never been greater. If I can contribute even a small part to shaping a more just and culturally aware generation, then every struggle along the way has been worth it.

Thanks for sharing that. So, maybe next you can tell us a bit more about your work?

I am an anthropologist and sociologist dedicated to creating educational materials for children. Plain and simple, I love identifying gaps in textbooks and transforming those missing pieces into fun, accessible, and engaging content. My goal is to provide children with resources that not only educate but also encourage meaningful conversations at home, helping them grow into well-rounded, accepting, and kind adults.

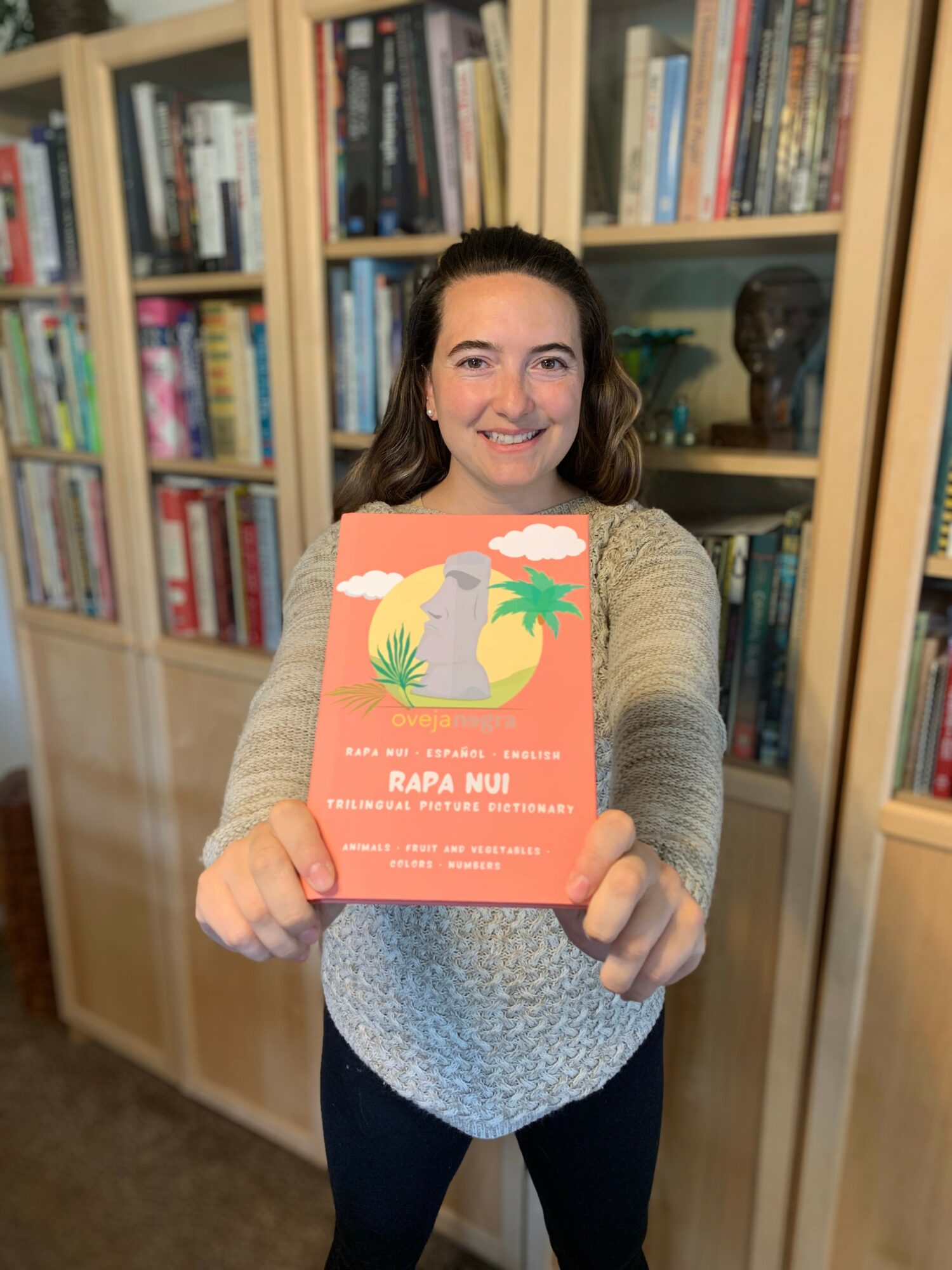

I am best known for my trilingual picture dictionaries (English-Spanish-Indigenous languages), as well as my books on art history and ethnography, particularly my work on Rapa Nui. Recently, I took a major leap into writing for elementary and middle school students, which has been both a challenge and an incredibly rewarding experience. Transitioning from early childhood materials to more complex subjects required me to rethink how older children engage with information. I’ve had to immerse myself in their world—researching their interests, the games they play, and the ways they interact with learning—to ensure my content is relatable and engaging.

Currently, I am publishing books on civics, American history, and Khmer legends, each of which has pushed me to think from the perspective of children in different age groups. As a mother, I often look at my own young children and reflect on how I would introduce these subjects as they grow older.

What sets me apart is that my work is deeply rooted in filling the gaps—bridging what children learn in school with the knowledge that is often omitted or, in some cases, actively banned. It is astounding to think that Indigenous cultures and histories could be erased from American education when they are fundamentally intertwined with the nation’s story. My work also serves as a bridge between past immigrant generations and the identities of today’s children, helping them connect with their heritage in a meaningful way.

At its core, my mission is about representation, accessibility, and empowerment—ensuring that every child has the opportunity to see themselves reflected in the stories they read, the languages they learn, and the history they are taught.

How do you define success?

The definition of success has changed radically for me over the years. When I was in college, success meant being a published author, gaining recognition, and seeing my name in interviews. But as my work evolved from a personal project into a calling, my perspective shifted. Today, I define success as the ability to take an idea from inspiration to completion—the passion and possibility of bringing what’s in my heart into tangible form.

I can’t say for certain if I will ever be widely recognized as an author or if my writing will ever provide a stable salary. Of course, that would be nice. But recognition isn’t what drives me—it’s the calling that has guided every major step of my journey. It’s the same calling that led me to study anthropology and sociology, that took me to Washington, D.C., to conduct research for the Smithsonian, that pushed me to leave the U.S. and learn from the Quechua people in Peru. It’s the same force that has fueled my work in environmental, economic, and educational justice—whether through advocacy, policy writing, or community organizing. And it is the same calling that now drives me as a mother: bridging.

Bridging ideas.

Bridging cultures.

Bridging voices—from communities to policymakers.

Bridging school materials with cultural knowledge.

My purpose is to connect worlds, to make knowledge accessible, and to ensure that the stories, languages, and histories often left out of mainstream education find a place in children’s learning.

I never imagined this life for myself when I was a rebellious teenager protesting outside the San Diego County Office of Education. Today, I am a stay-at-home mom, running my own publishing company, writing books that I believe in. But in every way, I am living my dream. I wake up each day excited to research, create, and complete the next project. I love what I do.

Will this change over time? Absolutely. My children are still young, and they need me more now than they will in the future. My biggest limitation at the moment is time—but that, too, will shift. And when it does, my version of success will evolve once again.

For now, I measure success not in external validation, but in the joy of creation, the impact of my work, and the bridges I continue to build.

I was once asked, What would you do if you knew you would fail? If I knew that what I was creating would never be considered “successful,” would I still do it?

My answer was simple: I would still write my books. Even if they were never recognized, even if they never reached a wide audience, I would keep writing—because that is what my heart and soul are meant to do.

Ironically, that question gave me clarity. It reaffirmed that I am exactly where I am supposed to be. My work doesn’t come from a need for recognition or validation—it comes from an unshakable desire to follow my heart, to create, to educate, and to bridge cultures through storytelling.

Success is not the reason I write. Passion is.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.ovejanegrakids.com

- Instagram: @ovejanegrakids

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ovejanegrakids