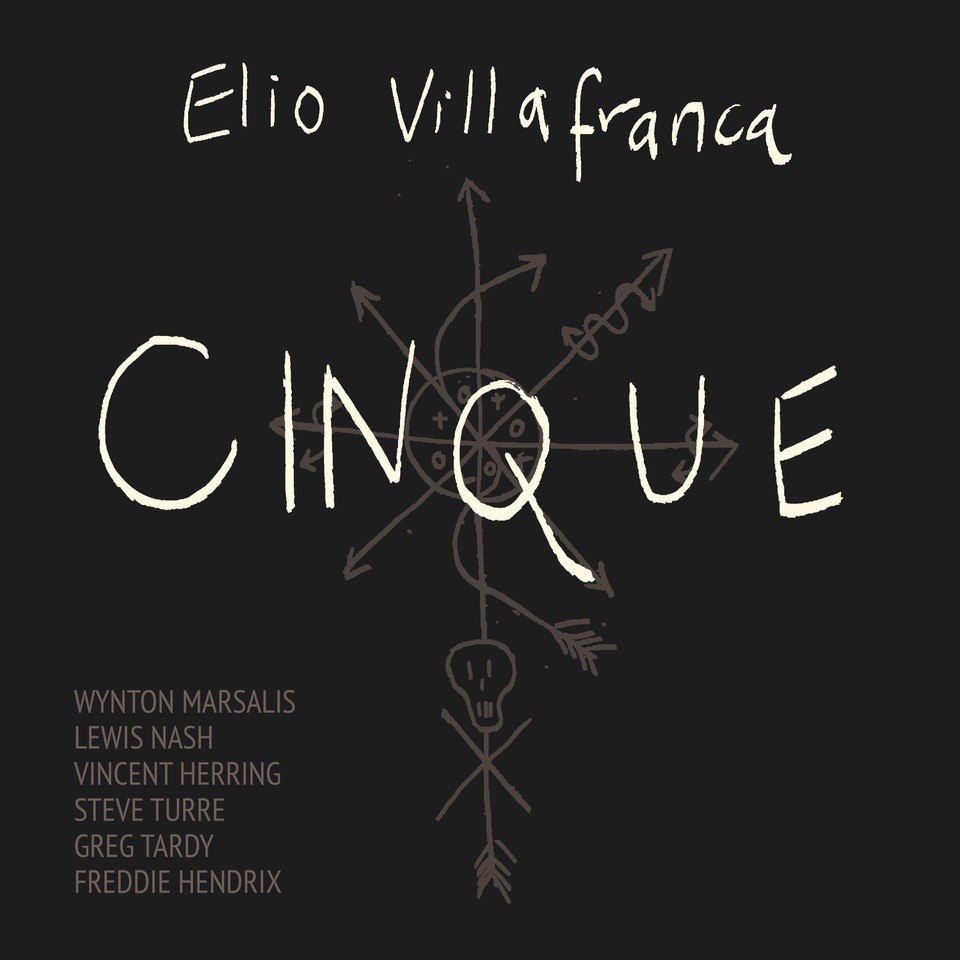

Today we’d like to introduce you to Elio Villafranca.

Today we’d like to introduce you to Elio Villafranca.

Hi Elio, it’s an honor to have you on the platform. Thanks for taking the time to share your story with us – to start maybe you can share some of your backstories with our readers?

I was born in a tobacco area in Cuba, in a town called San Luis, in Pinar del Rio.

Our house was in the center of town, right behind the courtyard of the Casa de la Cultura [House of Culture, a community center], so I had access to all sorts of musical activities that were happening there at the time.

When I was in elementary school, I enrolled in after-school art programs at the Casa de la Cultura. First, I did the painting for a year, then I switched to playing the guitar.

Our teacher at the center was a graduate of the Music Conservatory in Havana, and he taught classical guitar pieces. I fell in love with those pieces, and I decided that I wanted to go to music school to learn to play the guitar well. So that was my first serious introduction to music.

The other type of music I encountered in San Luis was the one played by the workers at the tobacco farms. They were not musicians by profession or by official training, but they played a lot of music, on a type of drum called the Tambor yuka, which is a drum of Congolese origin.

That music was played on the streets and also in the backyard of the Casa de la Cultura as part of the cultural programs, but it was not taught in any classes. When the farm workers played music in the yard or prepared the drums from the avocado tree trunks, I loved to peek over the fence and watch them work… I loved watching the flames and hearing the rhythms.

African drumming has a religious aspect to it, yes, but the Tambor Yuka is not actually a religious instrument, it is a drum that was used for communal gatherings, you would say parties today. The dance that goes with that drum became the basis for the rumba, later on.

The Tambor Yuka is also believed to be the first drum played on the island [of Cuba], because the Native American people of the Caribbean islands did not use drums, at least not according to the recorded or inherited traditions that we know about.

Going back to my formal education: when I was 11 or 12 years old, I enrolled in the [regional] music school for children, which was in Pinar del Rio. I wanted to play the guitar, but they had no more available spaces for guitar students, so I settled on percussion, which I had imagined to be like the drums I knew from San Luis.

But the music education in the school was strictly classical, so their percussion program had nothing to do with the drums I had known before. I was disappointed. Those were tough years, especially in the beginning, living in a boarding school, far away from my family. It took me a while to get used to that.

This school was the place where I started playing the piano, it was part of the music program for every student. I liked the piano and got more and more involved with it, but it became my instrument of choice only later on.

I went to high school in Havana, to the Escuela Nacional de Arte, which is a specialized school for music, visual arts, drama, and dance. During those years, I was playing the piano (keyboard) for a rock band, and I stayed with them for eight years. We toured a lot, in Cuba and in the Caribbean. But up until my university years I had not encountered jazz at all. My main exposure to music was classical and rock and roll, with the informal Congolese influence from my town.

After high school, I applied to the Instituto Superior de Arte [the institute of highest education for music in Cuba, a competitive university with a large campus in Havana]. I was worried that I would not be accepted as a percussionist, so I decided to also apply as a composer, hoping to be accepted at least for one of the two specializations.

I was accepted to both, as I won first place in the entry competitions for both composition and percussion, which was a big deal. That year, only two people were accepted for composition, one of them was me. I decided to take on a double major, which is rarely done.

My dad told me that this was crazy, but I knew that I could do it and I did, I graduated with two degrees, one in composition and one in percussion. And I played the piano, in addition to that.

I heard about jazz through a friend from San Luis who played the alto saxophone, and who suggested that I go to the annual international jazz festival in Havana. I went, but at first, I was not really impressed by anything until I saw Richie Cole play with his group.

This was in 1988. I think that seeing him play was the most liberating thing for me, ever. I remember that he was playing blues, he sang, and as I watched the pianist of the group play with that incredible amount of freedom, I knew that what I wanted to do was that, to play like that, to become a jazz pianist.

After school hours, students at the Instituto would get together for jam sessions and I started to attend them; I was dying to be part of that scene. The problem was that they had many percussionists already at the sessions, all of the great players, so there was no room for me.

The only thing that was left was a piano because nobody could play it well enough. Then one day, out of desperation, I took the piano and I played for them. It must have worked really well because they kept asking me to return and play the piano. That is how I became the pianist at the jam sessions.

I remember this was the point when I made the conscious decision to become much better at the piano than I was at that point, I told myself that if I really want to become a pianist, I better do it well. I talked to my piano teacher who agreed to create a personalized program for me because I did not want to quit the percussion program. And this is how it started. I put a lot of time into the piano… a lot of time, skipping meals sometimes to secure a good piano to practice on.

At the time there was no jazz played in Cuba outside the yearly festival, so you had to get your jazz education by buying cassette tapes at the black market, where they went for a very high price. Our teachers at the Conservatory, who had a purely classical musical mindset, did not support us at all.

For them, jazz was not music. Alongside the cultural bias, there was an element of politics in this, because Cuba is a communist country many of our teachers at the university were Russian or trained at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory of Music in Russia. These teachers saw jazz as a symbol of America, as the music of the enemy, some form of decay.

But I persisted, I formed my own jazz band and we started auditioning for the annual jazz festival in Havana and we got accepted to play, each year. That was great exposure, the international festival, as bands from other countries came, alongside the professional ones from Cuba. But my band was the only student band at the festival.

Jazz for me is freedom, it is free creative expression. Freedom, period. It is not that there are no rules in jazz because there are. The point is really that within the structure of the rules I can choose a direction and interpretation for myself.

You know, when you play a classical music piece, the closer you get to what the composer’s mindset was when writing it, the better your interpretation is considered to be. Your interpretation is judged by the original. In jazz, it is not like that at all.

Jazz is freedom within a language and structure.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

It has not been an easy path.

I encounter many obstacles along the way, being an immigrant, and a person of color. However, the biggest obstacle for me was adjusting to a very capitalistic society.

In Cuba, I learned everything related to socialism and communism, while any thought about capitalism was discouraged. This, amplified by the fact that I came here alone, made my adjustment period even more challenging.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar what can you tell them about what you do?

I’m a jazz pianist, composer, and a cultural activist. My work involves creating engaging interactive musical experiences involving lectures, demonstrations with world-class artists, dance, muralists, and other means to achieve the kind of artistic space I believe is essential for authentically communicating to audiences the values shared by the cultures with which I identify.

The variety of rhythms used in the music I create, based on traditions of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, help to communicate the historical context in a modern way that provides greater meaning to the work and allows the way of life known to me to be more accessible, appreciated and understood by all audiences.

My artistic practice is inspired by my Cuban upbringing alongside the goal of creating a diverse and inclusive world, one where sounds, stories, and images guide us to see our shared humanity and to cross socially created boundaries and lines.

A painter at a young age, I became a musician and have worked as a composer and pianist for almost thirty years. The combination of melody and rhythm I use in my compositions is based on the traditions of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora and it communicates our historical experience in a modern way, to be accessible to all audiences.

I have several proud moments: I’m a Steinway Artist, a 2021 Guggenheim Fellowship recipient; a two-time Grammy nominee; a 2019 Downbeat Critic’s Poll Rising Stars Pianist; winner of the 2018 Downbeat Critic’s Poll Rising Stars Keyboard; first Cuban-born recipient of the Sunshine Award (2017).

Founded to recognize excellence in the performing arts, education, science, and sports of the various Caribbean countries, South America, Centro America, and Africa; and a recipient of the first Jazz at Lincoln Center (JALC) Millennium Swing Award! in 2014.

Risk-taking is a topic that people have widely differing views on – we’d love to hear your thoughts.

As a jazz artist, I see the concept of risk differently than the average person.

When we, jazz artists, take a risk, musically speaking, we feel that that action would open the door for another possibility. We tend to embrace it! It is at that moment that jazz actually manifests its true value. Freedom!

This is the area where I take the most risks in life, which could also be applied to the risk I took by coming to the US on my own. Like in jazz, I embraced it, and here I’m.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.eliovillafranca.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/eliovillafranca/?hl=en

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/eliojazz

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/eliovillafranca

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/ElioVillafranca/videos

- SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/elio-villafranca

- Other: https://open.spotify.com/artist/0Q4WdT8DgUM4uvuGk3eWF8

Image Credits

Image Credits

Berta Jottar, Carolin Rechberg, and Kasia Idzkowska