Today we’d like to introduce you to Samira Shiridevich.

Hi Samira, we’re thrilled to have a chance to learn your story today. So, before we get into specifics, maybe you can briefly walk us through how you got to where you are today?

My story begins in Iran, a country with thousands of years of history, culture, and tradition. Growing up there, I was surrounded by beauty—historic architecture, the vibrancy of Persian art, the richness of calligraphy, and the diversity of landscapes where you could reach the desert in an hour or the sea in three. I loved exploring these traditions and saw how deeply they shaped people’s identities and ways of seeing the world. At the same time, I also grew up with limitations, especially as a woman. There were many things I longed to do that were not possible—like cheering in a soccer stadium, walking along the beach with my hair in the wind, or speaking openly about my disagreements with the government or religious structures. I wanted to express myself freely, both as an individual and as an artist, and I often felt the boundaries around me tightening.

Even though I loved my family, my community, and my country, I decided to leave Iran in order to pursue a different definition of freedom—one that allowed me to think, speak, and create without fear. That was one of the hardest decisions of my life: choosing to leave everything I loved behind to search for a future that felt truer to me.

When I came to the U.S., I carried with me both my cultural pride and my questions about identity. For the first time, I encountered the confusing reality of not knowing what “race” box I belonged to on legal forms. I wasn’t white, Black, Asian in the American sense, Arab, or Hispanic. I was Persian, Iranian—and yet there wasn’t a space for that. These identity struggles, along with the stereotypes I encountered about my country (like people assuming Iranians still ride camels or that women cannot work or drive), deeply influenced how I began to think about design. I started to see design not just as a profession but as a way of challenging simplified narratives, broadening perspectives, and giving space to voices that don’t easily fit into categories.

I pursued an MFA in Design and Visual Communication at the University of Florida, where my academic journey really allowed me to connect my personal story to my design practice. My first big project here was a visual essay analyzing global freedom posters through semiotics. I wanted to understand how designers across cultures had used visual language to advocate for human rights and expand people’s ideas of freedom. This was not just academic—it was personal. It was my way of asking: how can design help people see beyond their limitations and imagine new possibilities?

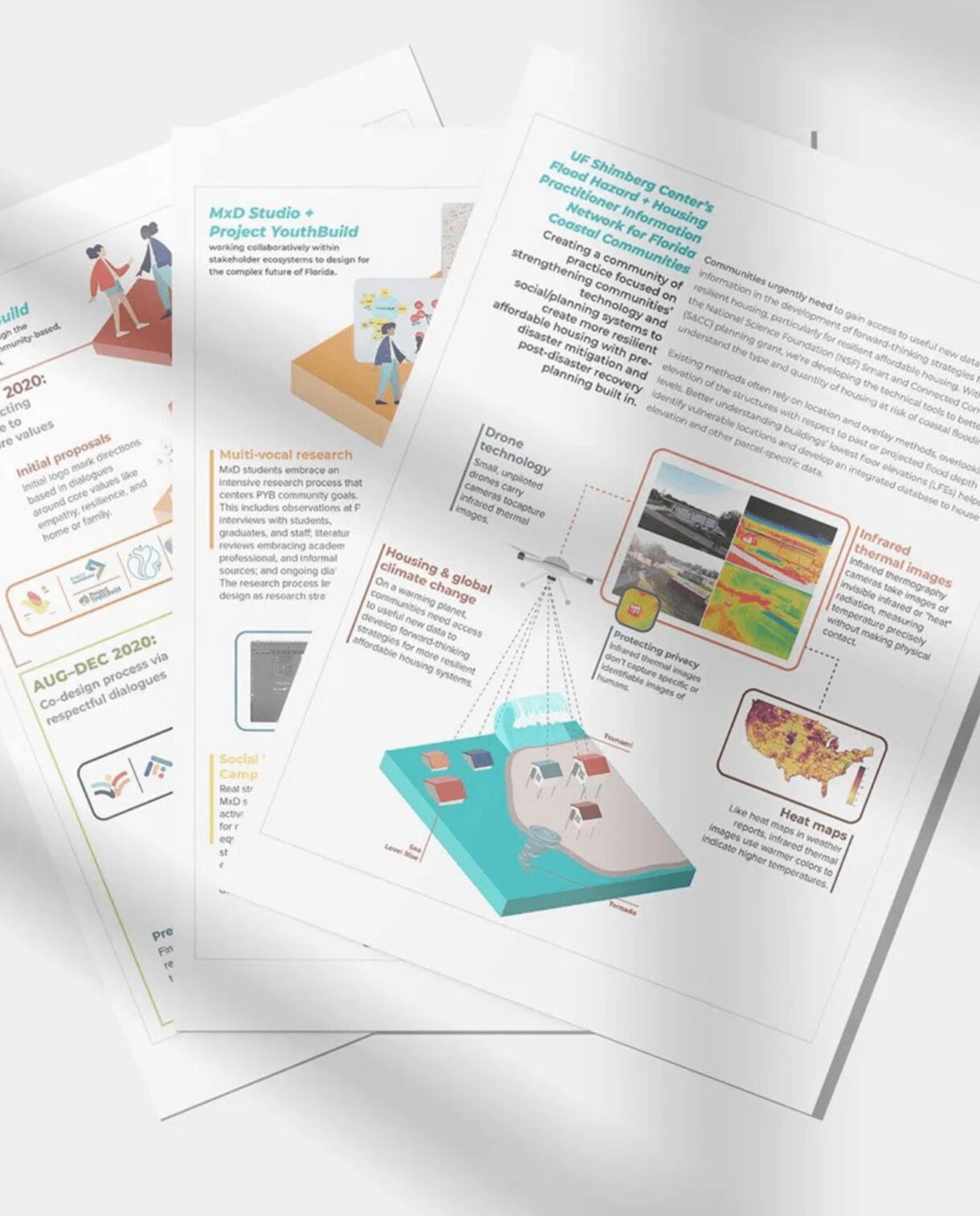

That question led me into deeper community-engaged work. I collaborated with Project YouthBuild in Gainesville, working with young people who had been pushed out of traditional schools. Together, we co-designed an interactive game and community asset map to help students build reciprocal relationships with their neighbors and uncover hidden strengths in their community. That project, which became my MFA thesis called CONNECT, taught me that design can be a bridge: between generations, between communities, and between people who may otherwise feel unseen.

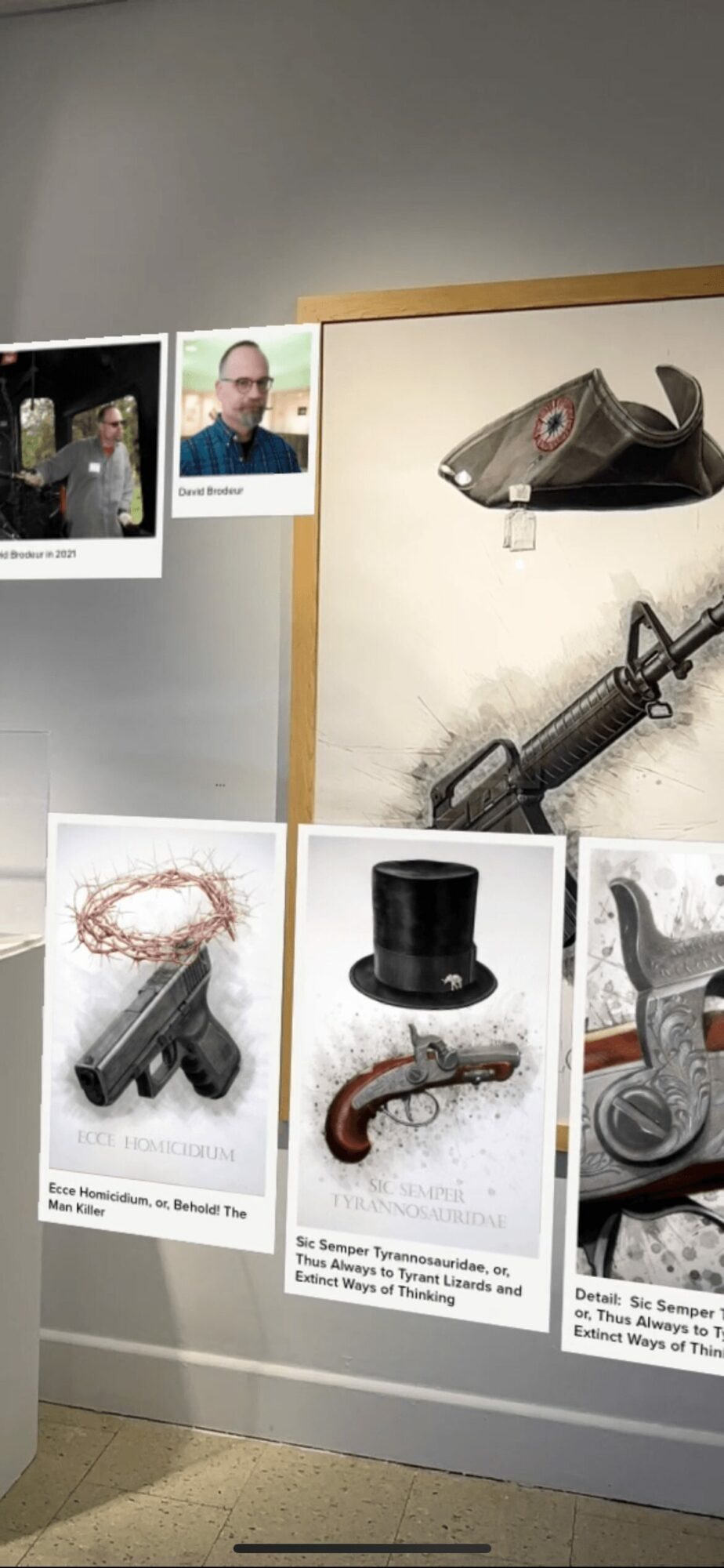

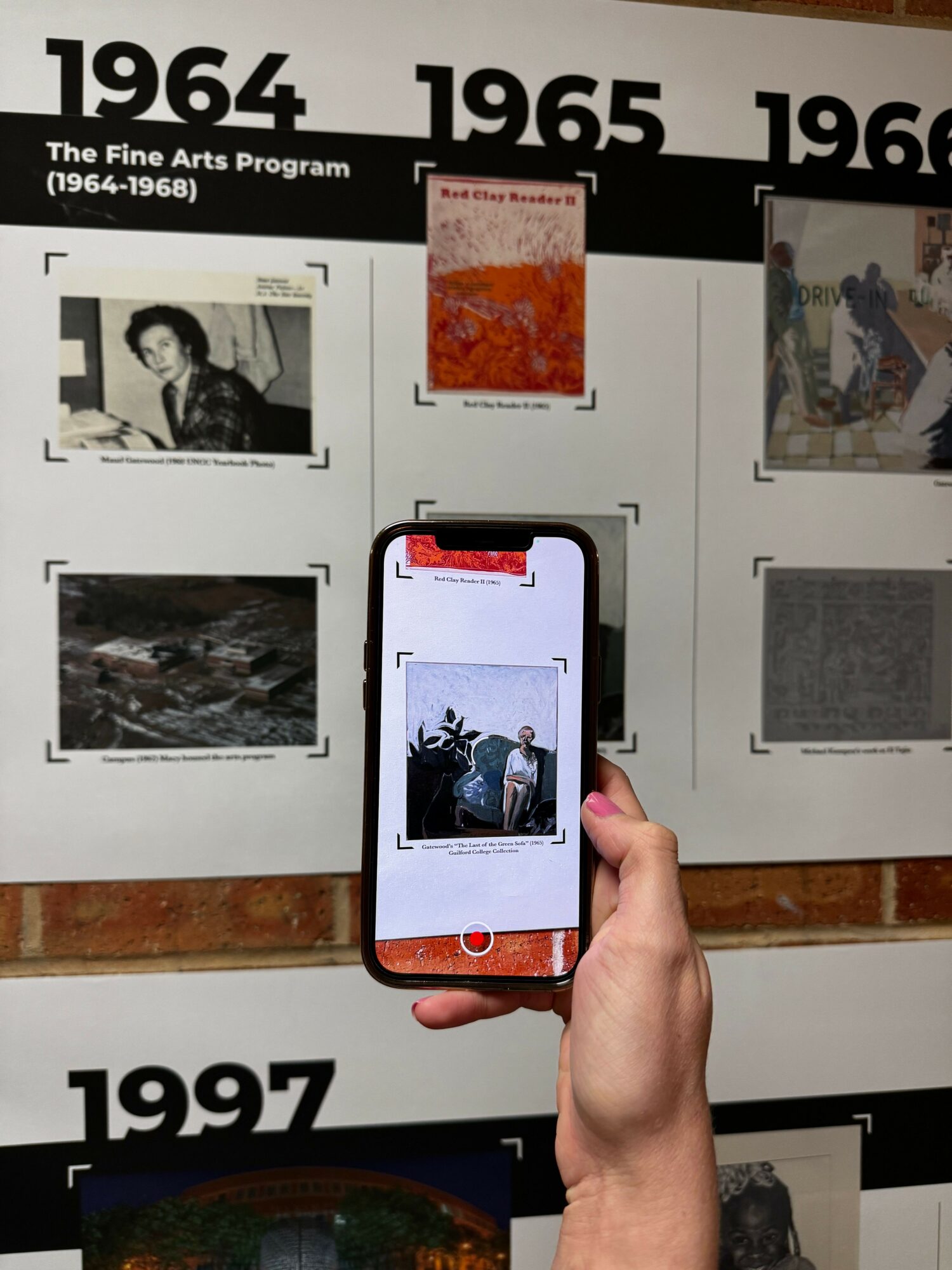

Since then, my work has consistently centered on co-design, horizontal methods, and participatory practices. I believe in designing with people rather than for them, and I’ve worked on projects that range from immigrant storytelling to community asset mapping to interactive, technology-driven experiences. My goal has always been to use design as a tool for empathy, freedom, and empowerment.

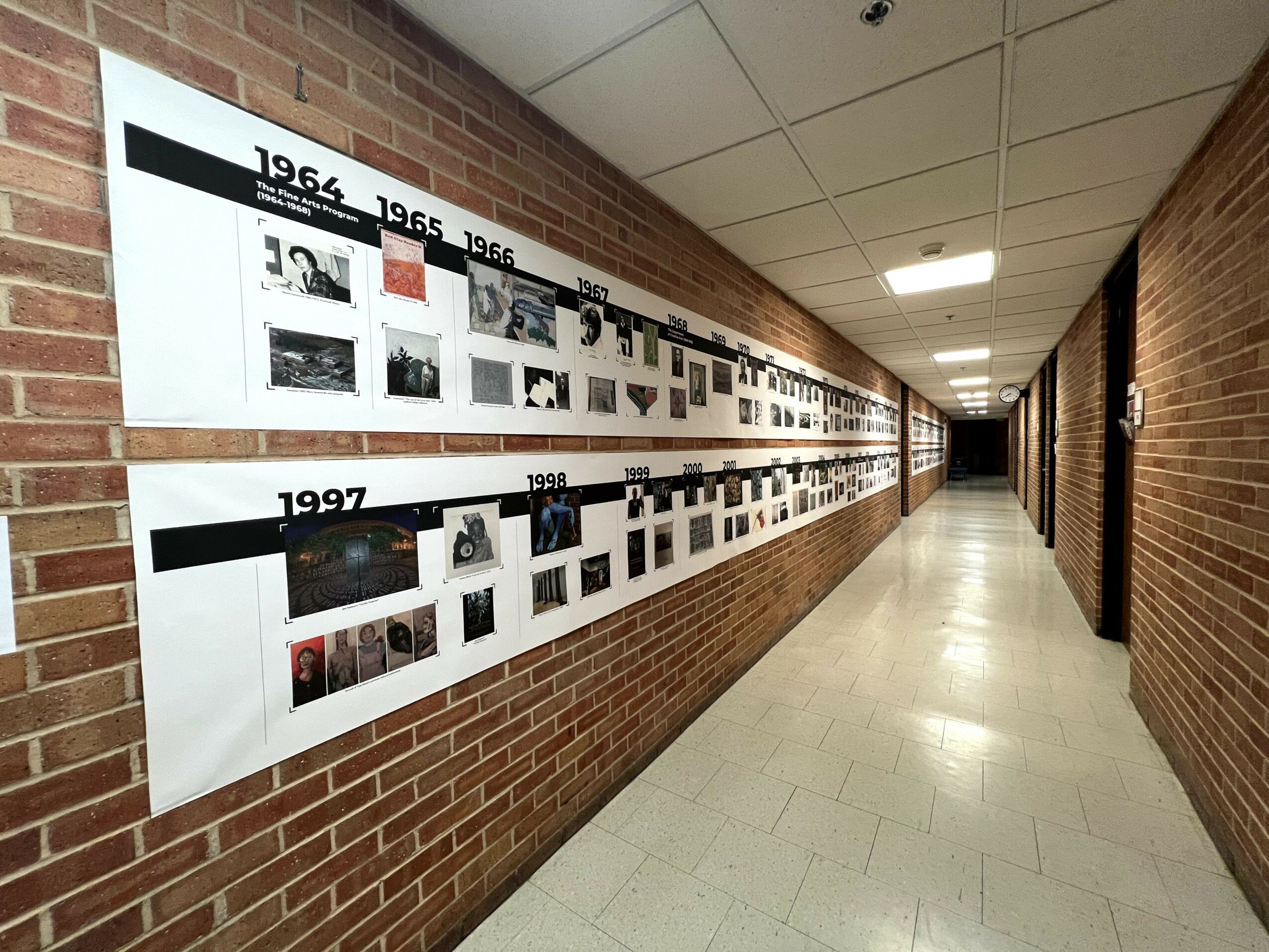

Today, I’m an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at UNC Charlotte. In my teaching, I try to pass these values on to my students, encouraging them to see design as more than aesthetics—design as storytelling, as dialogue, as a force for social change. In my research, I continue to explore how tools like mapping, data visualization, and even augmented reality can give voice to underrepresented stories and connect communities across differences.

Looking back, my journey has been shaped by contrasts: love and struggle, loss and discovery, tradition and transformation. What connects it all is a belief that design has the power to reframe freedom, amplify unheard voices, and create spaces for more empathetic futures.

I’m sure it wasn’t obstacle-free, but would you say the journey has been fairly smooth so far?

It has not been a smooth road. One of the biggest challenges was learning how to navigate identity in a new cultural context. I often felt caught between categories that didn’t reflect who I was, and I also encountered stereotypes about my country that felt frustrating. On top of that, this was my first time living in a place surrounded by such a diverse group of people, and I wanted to be respectful while also learning how to understand and engage with cultures different from my own.

There were also practical struggles—adapting to a new language, building a career far from family, and facing the limitations of visa status. While I was dealing with these, events in Iran often made life even harder. Every time people in Iran rose up to protest, the government shut down the internet. During those times, I couldn’t contact my family, and I felt caught very far from home, not knowing if they were safe. Those moments were some of the most difficult, because they combined distance, fear, and helplessness.

Through all of this, I learned how important patience, trust, and consistency are in building relationships and communities. None of it was easy, but each challenge shaped me into a more empathetic, persistent, and thoughtful designer and educator

Thanks – so what else should our readers know about your work and what you’re currently focused on?

My work sits at the intersection of design, community, and social change. I am a graphic designer and educator, but I see design as much more than creating visuals — I see it as a process of listening, connecting, and amplifying voices that are too often unheard. I specialize in co-design and horizontal design methods, where instead of designing for communities, I design with them. This means engaging people directly in the process, centering their stories, and creating tools that allow them to represent themselves on their own terms.

Much of my research and creative practice has focused on immigrant and youth communities, exploring how design can be a bridge between people and cultures. For example, my MFA thesis project, CONNECT, was a collaboration with Project YouthBuild students in Gainesville, Florida. Together, we co-designed an interactive game and community asset map to help build trust between young people and their neighbors, particularly elderly residents in the community. What I am most proud of is not just the final product, but the process — the laughter during game testing, the stories shared across generations, and the sense of empowerment students felt when they realized they could shape their own narratives and be seen as assets to their community.

I think what sets me apart is that my work is grounded in both personal experience and professional practice. Growing up in Iran, where freedom of expression was restricted, I developed a deep awareness of what it means to not have a voice. That personal history makes me especially sensitive to issues of representation, belonging, and agency, and it’s why I am passionate about using design to challenge stereotypes and broaden horizons. My projects often combine traditional design practices with participatory methods and new technologies — whether through mapping, storytelling, or even augmented reality — to create experiences that are both visually compelling and socially impactful.

Today, as an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at UNC Charlotte, I bring these values into the classroom. I encourage students to see design not just as a set of technical skills but as a way of understanding people, asking better questions, and building inclusive futures. For me, design is about creating spaces for dialogue, empathy, and change — and that’s the thread that runs through everything I do.

What sort of changes are you expecting over the next 5-10 years?

I believe the design industry is at a turning point, and the next 5–10 years will bring even greater shifts. Technology is rapidly expanding what is possible—AI, immersive media, mapping tools, and data visualization are transforming how we tell stories and represent complex issues. These tools won’t replace designers; instead, they will extend our ability to explore ideas, while the real heart of design will remain rooted in human perspective, creativity, and storytelling.

At the same time, design is becoming more about responsibility and representation than just aesthetics. I see the field moving toward approaches where people are active participants in shaping the work, not just audiences consuming it. In my own projects, I’ve seen how powerful it can be when youth, immigrants, or community members take ownership of the design process, and I think this model will become more common.

I also believe that topics like sustainability, access, and freedom of expression will take on a more central role. As global challenges continue to grow, design will need to respond with solutions that are both visually compelling and socially responsible. For me, the future of design lies in combining technological innovation with a deeper commitment to representing real voices, connecting people, and creating meaningful change.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.samidevich.com

- Instagram: @samishivich

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/samirashiridevich